What is the ideal software delivery experience? Apple figured it out initially with the iPhone and later with other products, and Microsoft followed suit beginning with Windows 8. The App Store and the Windows Store are curated, safe spaces from which to purchase and download applications, and these stores provide fantastic user experiences. (Other platforms have package management systems with varying features and capability, but I have no experience with those, and my focus is on Windows software deployment.)

With an app store, an application and all of its updates come from one place. Because all of the apps available there go through a validation process, users can feel confident that they are not downloading malware. The apps install without prompting the user for information, and they work immediately. If an app requires configuration, it prompts the user and can save the configuration to a cloud storage location so that the app is immediately usable upon whichever device the user runs it. Software just works, and users can quickly get to the business of using the software instead of installing and configuring it.

The Desktop Difference

Contrast this with the installation and usage experience for traditional desktop applications. I’m going to focus on software for the Windows operating system for the rest of this post. Here are some typical steps to installing and using software.

- Find the desired software somewhere on the Internet and buy it. If it is free, hope that you were not tricked into downloading malware instead of the software you wanted.

- Run the installer. This is probably an executable program that must be run with administrative credentials, so you are basically giving complete control of your computer over to the setup program.

- Answer configuration questions asked by the setup program. You may not be confident in your answers or may not have any idea how to answer some of them.

- Restart your computer and then spend 20 minutes re-opening all of your programs and browser tabs.

- Notice that the installer has put one or more icons not only on your Start menu, but also on the desktop and on the taskbar.

- Further notice that the notification area shows that the new program is already running, even though you didn’t specify this.

- Run the new program, and answer additional configuration questions asked by the program. Again, you may not know the answers to these questions.

- Take a tour of new features!

- Dismiss a “Did you know…” pop-up message or maybe a new feature advertisement pane.

- Actually use the program.

- Realize that you also need the program on another computer, and begin the whole process again.

This may seem extreme, but all of the above behaviors are commonplace. If you decide to uninstall a program, you may have to go through these steps.

- Uninstall the application.

- Specify options for removal. Should all components be removed? Should data be removed? You don’t really want to uninstall the program, do you?

- Complete a survey about why you uninstalled the application.

- Restart the computer and then spend 20 minutes re-opening all of your programs and browser tabs.

- Discover that some components of the application are still installed but that there is no way to uninstall them through standard procedures.

Here is a concrete example that I observed and recorded in early 2015. There is one particular program that nearly everyone in my organization wants that, when it installs, puts shortcuts on the Start menu, on the desktop, and on the taskbar. Then, even if you delete the desktop and taskbar icons, when another user runs the program, it recreates those icons in that user’s profile. It even uses (or at least did so in early 2015) an undocumented feature of Windows Setup to insert itself into the first-logon experience so that it can create these icons before the user has ever decided to use the program, causing a two-second delay in the first logon experience. Then, when a user actually wants to run the program, the first thing it does is try to take over being the default handler for its particular file type. When the program actually opens, it displays a tab with a tour of new features and tries to get the user to create an account with the manufacturer. This entire experience is bad enough for regular users, but it is truly horrible for lab or classroom environments in a school or university because every single user logon is probably that user’s first time logging onto a given machine. What is this malware, you ask? It’s Google Chrome.

It didn’t have to be this way. Microsoft has published application user experience guidelines for years and years, and it has also had a “Designed for Windows” logo program for software since the Windows XP days (2001) and perhaps even before that. Unfortunately, these guidelines and programs seem to have been largely ignored by software vendors and their customers. I have some ideas about why this happened and thus why software distribution is in such a sorry state today, but my purpose here is not to assign blame; rather, I want to discuss the problems and arrive at some principles to guide the creation of solutions. I think the Apple App Store and the Microsoft Windows Store are reactions to the resistance of independent software vendors to write good software; these app stores codify into “law” the kinds of behaviors that have always been prescribed by user experience and logo program guidelines and make them non-optional, since the operating vendor acts as the gatekeeper for what appears in the store.

The installation, usage, and uninstallation steps listed above are disastrous for large-scale rollouts of software in an organization. It is disturbing to consider the amount of money spent on wages to employees that are not actually doing any work because they are struggling with bad software. If something goes wrong, they will hopefully call the organization’s help desk for assistance; this may reduce downtime, but it requires that another employee be on the other end of the telephone line to help with the issue. If your organization’s IT and top management are even mildly interested in data security and keeping support costs low, most users will not have administrative access on their machines and will thus not even be able to install software themselves. This leaves the deployment to the IT staff using any number of deployment tools available on the market, but there is still a lot of work required to deploy software in a way that mitigates the behaviors described above. In organizations with hundreds or thousands of client computers, manual installation of software expensive and error prone, so we must rely upon software deployment tools. There are numerous deployment and package management systems available, but they cannot help fix the fundamental problems built into software vendors’ setup programs by design. That task falls to the IT professional.

Guidelines for Great User Experience

My goal is to make the desktop application installation and usage experience as close to the idealized app store experience as possible. To guide the work toward that goal, some reference documentation and some specific principles are helpful.

Microsoft provides some great documentation on the proper behavior of Windows applications throughout their entire life cycle—installation, use, and uninstallation. See the following resources at the Windows Dev Center for the most recent versions of the Windows application design and certification guidelines:

Everything written by Rob Mensching or anyone else on the WiX Toolset team is also fantastic source material for the way installers ought to work. With that knowledge, we must then set about the task of bending the software to our will, as the tagline of this blog suggests, by fixing or working around the terrible installers published by software vendors, so that we can provide the app store experience to users.

Here is my list of guiding principles with explanations.

- The software must be able to be installed silently—that is, without any user prompts. This provides that app store-like experience of one-click installation. It also makes it possible for IT administrators to deploy software without user involvement.

- The software must be able to be installed without forcing the computer to restart. A forced restart could cause data loss, and that’s obviously unacceptable.

- Eliminate all first-run experiences. This one is sometimes difficult. Many programs want to interrogate the user the first time they run, but this is incredibly frustrating for the user if the application is updated often or in public computing spaces where a user may never sign into the same computer twice (thus getting the first-run experience every time).

- Don’t ask the user questions he/she cannot answer. This is a special case of first-run experiences, but it bears mentioning separately. In my observation, there is often a clear mismatch between the level of understanding a software developer expects a user to have about a piece of software and the level of understanding that the user actually has. Many applications ask users questions that they just don’t know how to answer.

- As a consequence of the previous four principles, provide any required configuration information either in the application deployment process itself (preferred if possible) or through an outside mechanism like Group Policy or Group Policy Preferences.

- Don’t allow an application to overwrite user preferences.

- Don’t allow an application to put icons on the desktop or the taskbar. This is a special case of user preferences, since these locations are intended to be for the user to customize. The only appropriate place for an application to put a shortcut is on the Start menu.

Some applications will easily work within these principles. If an application is packaged as a Windows Installer package, you’re already in pretty good shape. Unfortunately, many are provided as setup executables, and these require a variety of techniques to tame. Future posts will focus on individual applications that are common to many organizations—specifically, free readers, players, and browsers—and how to package them in System Center Configuration Manager so that the user experience is as much like an app store as possible.

An Easier Way

There are commercial products available to take care of free apps. I know people that subscribe to one of these services, and they are very happy with it. There are several reasons why an organization may not be able to do this though. An organization that only needs one or two apps covered by one of these auto-updater programs might have trouble justifying the cost for so little benefit. There may be concerns about performance or the additional management burden of another agent program running on every computer in the organization. There may also be security concerns, legitimate or not, that result in blocking such a subscription.

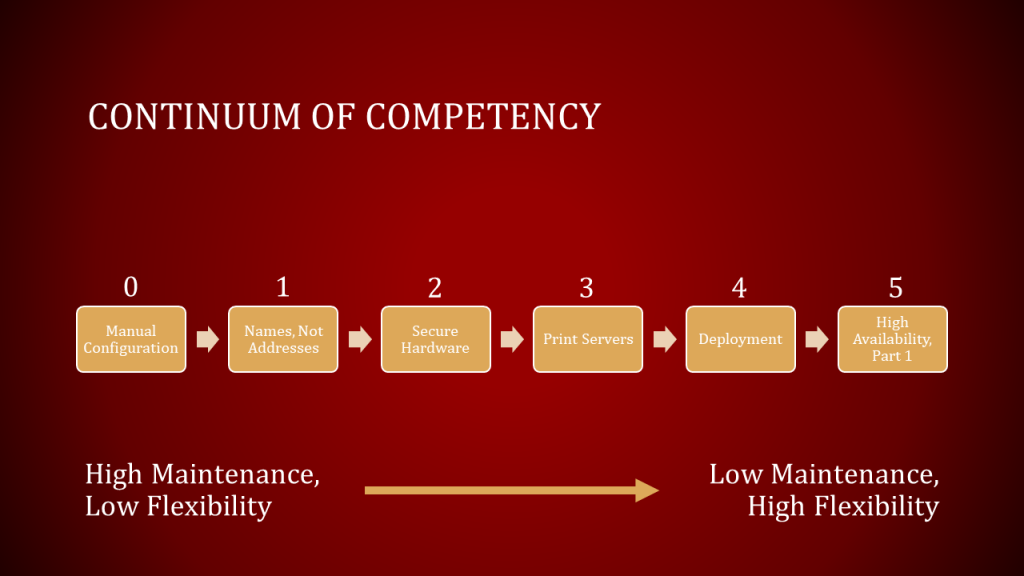

In any case, free readers, players, and browsers are useful for exploring the ideas described above in the context of a specific deployment tool (Configuration Manager) and practicing the techniques needed to achieve the goal of an app store-like application experience. Then when an important, paid-for, poorly-behaved app comes along, the principles and methods needed to fix it will be well understood.